LPL RESEARCH PRESENTS outlook mid year 2022-Midyear Downshift for Macroeconomic Environment

Economic growth will likely downshift in the latter half of 2022, reflecting a slowdown in real spending as a consequence of elevated, persistent inflationary pressures. Recession risks are increasing but our base case is no recession this year as consumers, particularly the upper-income ones, can sustain spending patterns from income growth, excess savings, and revolving consumer credit.

U.S. economy slowing, not shrinking

We believe the domestic economy will continue to grow this year. Other than the anomaly of a negative first quarter GDP print, we think the economy has sufficient momentum to offset the inflationary pressures. Our base case forecast includes an inflation rate that moderates as supply bottlenecks improve and we potentially get some closure to the Russian war with Ukraine. Our most likely scenario: the economy avoids a recession as forecasted growth surpasses 2% in 2022 with another downshift to under 2% in 2023 [Fig. 1].

Looking back, the U.S. economy took off in 2021, surging 5.7% after contracting by the most since the Great Depression at 3.4% the previous year. Last year, consumer spending was extremely robust, particularly on consumer goods as consumers flush with stimulus checks were still less inclined to spend on services. Goods spending contributed roughly 2.7 percentage points to the headline growth rate, the highest since 1955. While we do not think consumer spending will continue at this clip in 2022, the consumer will likely weather the headwinds of high prices and geopolitical uncertainty and support the overall economy throughout 2022, offsetting the expected decline in residential investment.

Flip the script

As it turns out, monetary policy might not necessarily be the main factor underneath growth or recession prospects. The consumer is the key variable. U.S. consumers, particularly the upper-income ones, might be the primary factor for the base case estimate that the U.S. gets a “softish” landing. Instead of only focusing on the probability that the Fed makes a policy mistake, watch consumer behavior—especially during these times of higher food and energy prices—as consumer spending makes up roughly 70% of the economy. Overall, consumer spending will likely slow during the latter half of this year as inflation pressures weigh on consumers and wage growth likely lags inflation. These factors in tandem will erode consumers’ real purchasing power. However, recent spending activity shows a fairly stable consumer. Real consumer spending rose 0.7% in April, the fourth consecutive monthly increase in real spending, before pulling back slightly in May. The job market is tight, supporting consumer spending from gains in personal income, but the real cushion for consumers comes from roughly $3 trillion in excess savings accumulated during the pandemic. To further pad personal spending, consumers will likely tap into consumer credit. We expect revolving credit demand to increase in the latter half of this year without reaching unstable levels since consumers hold much less debt now relative to previous cycles. After the Great Financial Crisis, consumers started aggressively deleveraging. Overall debt payments as a percent of disposable income declined and remained steady until the emergence of COVID-19 [Fig. 2]. Government pandemic assistance programs, including stimulus and forbearance periods, added volatility to consumers’ financial obligations. But if consumers are able to keep relatively low debt levels, we think the consumer can successfully navigate a period of rising borrowing costs without squelching spending.

Inventory rebuilding could fuel growth

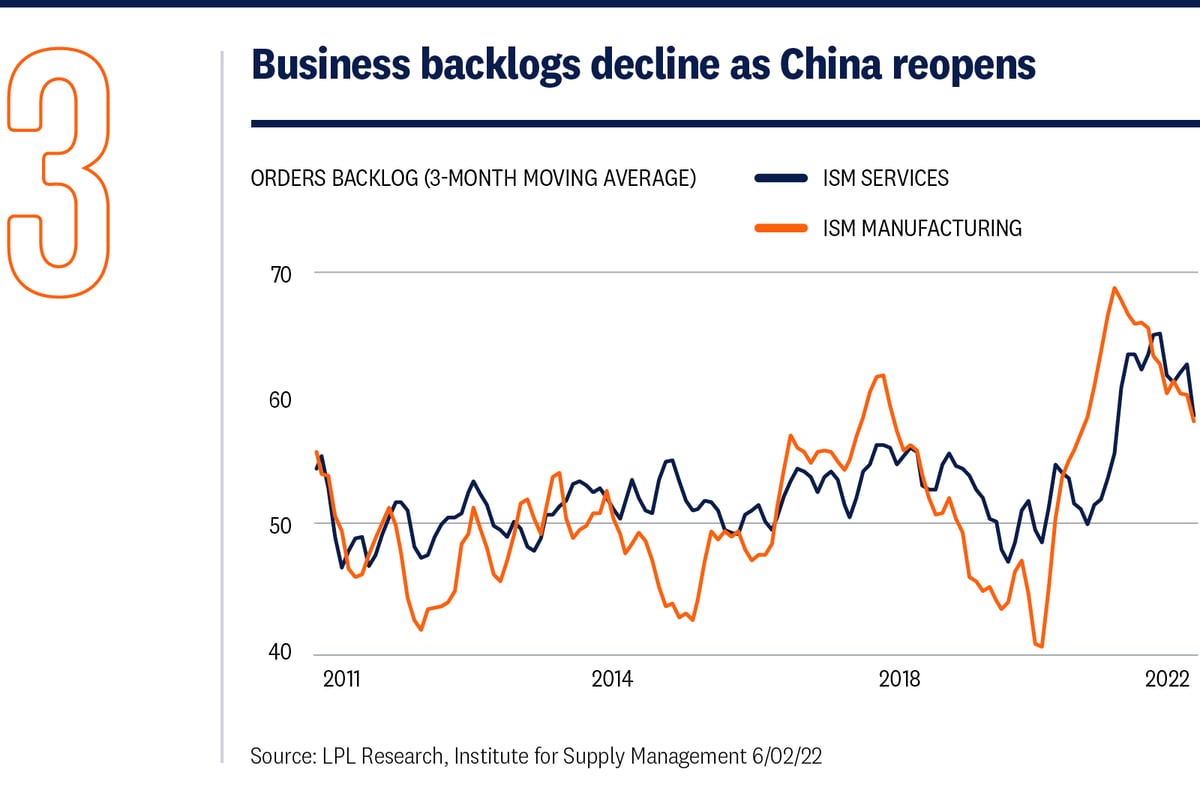

If supply bottlenecks improve, we expect to see firms restocking inventories, supporting underlying economic growth. Recent reports from the Institute of Supply Management show that order backlogs are declining for both the manufacturing and services sectors [Fig.3]. As firms have improved access to required inputs and as the transportation sector recalibrates to the current environment, the economy could likely see growth in the latter half of this year and avert a recession.

Inflation is still the wild card

Inflation rates will likely cool throughout this year, but the cool-down period will be long and slow and inflation will still very likely be above the Fed’s long run target of 2%. Improvements in supply chains have started to impact consumer prices [Fig. 4]. Technically, consumer price changes lagged by four months are 72% correlated with the New York Fed’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Gauge. Given the improvement in supply chains, inflation pressures should subside.

Potential drag on growth

A slowdown in residential investment will likely have a meaningful impact on growth this year. The slowdown could come from both the demand and supply sides as interest rates increase. The average rate on a 30-year fixed rate mortgage has risen over 2 percentage points since the beginning of the year and has created a damper on housing activity. Secondary effects from rising mortgage rates will likely slow consumer spending. At the beginning of this year, the principal and interest payment on a $300,000 loan at 3.27% was $1,309. At the end of May, the monthly payment rose by $366. As housing becomes a larger percentage of an individual’s budget, we will likely see a decrease in discretionary spending.

When we look at changes in borrowing costs we often focus on homebuyers, but higher borrowing costs also affect builders. High capital and labor costs are a current challenge for all builders, and high interest rates particularly impact developers who rely on the debt market for construction. Tighter financial conditions could eventually slow new home construction, putting a damper on home supply and residential investment. Inventories of new and existing homes are already low, and if builders slow the rate of construction, home prices will not likely decline as much as they did in 2006–2011 since current supply is low.

Risks to the outlook

A still unknown variable to our forecasts is the Fed’s shrinkage of its balance sheet, known as quantitative tightening (QT). The Fed will only allow its nearly $9 trillion balance sheet to shrink incrementally over time while also paying attention to the impact QT is having on the markets. The Fed has stated that QT could “replace” several rate hikes as a way to tighten financial conditions and help curb inflation, but the bigger risk is the Fed aggressively tightening and intentionally engineering a recession to slow down pricing pressures. Remember, it took two recessions in the early 1980s to put an end to inflation back then. The other risk could come from weakening consumer spending. As consumers become more concerned about future economic conditions, they may become less inclined to spend on consumer goods or services.